November 6, 2016

Dean Torges 1941-2016

On November 4, 2016, Dean Torges crossed the Great Divide. He was a loving husband, father, grandfather and friend and mentor to countless people around the globe. He was a gifted craftsman who would literally hand you the shirt off his back if you chanced to admire it. A number of years ago I shared a memorial written for an elderly friend of mine who had passed and Dean commented that it was the most eloquent valedictory as he had ever seen. I share this with you all below, in loving memory of my friend, Dean. — Admin.

To those I leave behind when I go:

Death is nothing at all. It does not really count. I have merely slipped away into the next room. Nothing has happened. Everything remains as it was. I am me, you are you, and the life we lived together is untouched and unchanged. Whatever we were to each other we still are.

Call me by my old familiar name. Speak of me in the easy way you always did. Put no difference in your tone. Wear no forced air of sorrow. Laugh as we always laughed at the jokes we enjoyed together. Play, smile, think of me, pray for me—a little.

Let my name be the household word it always was. Let it be spoken without effort, without the ghost of a shadow upon it. Life means all that it has ever meant, the same as it ever was. There is absolute and unbroken continuity. What is death but an unavoidable incident? Why should I be out of your mind because I am out of your sight?

I am but waiting for you—very near—just around he corner.

All is well.

All my love,

Dean

October 18, 2016

SOUP LINES

I'm in a hospital. Family and friends visit during the day. Steroid induced sleeplessness and the proximity of Death creep in for late night companions. When my eyes dim, we watch a cauldron of confusions and impurities bubbling on slow simmer—a potent, unsettling brew whose attraction I cannot escape.

The mixture moves in and out of focus. Sometimes I can see small craters where bubbles came and went. Sometimes it recedes into the ether. Gumbo, it seems to be, a lifetime's gather of indistinct animal and vegetable parts.

It's Monday now. Mary has been by my side since we arrived, Wednesday. My Una, she sleeps on a small, fold-out chair/bed at night. The light she brings is the disinfectant I pour over the ingredients, revealing what's safe for consumption. It's always been this way.

My daughters Beth and Cindy spend hours at a time visiting with me in the hospital, drinking the brew. I have some for my two elder daughters, but there are obstacles. One lives too far from here, and grieves for the lost opportunity, while the great sadness for the other is a heart and mind pursued and too often subdued by Fear, Anger, and Lost Faith.

I have hope for her without knowing how to guide her toward understanding, to recognize that deceptions propped against the brewing cauldron are not armored supports that protect the gumbo. Their pose does not earn them grateful partner status with the truth and the beauty of the brew. They incinerate. They are meant for gumbo fuel.

To exercise I limp around the hospital hallway with a cane, massaging my right-side cancer-weakened femur into absorbing a titanium support rod shoved down it two months ago. I also wear an eyepatch to mitigate the double vision effects of a palsied left eye. My voice is gone to a whisper, metered by COPD pauses, the residue of radiation and chemo treatments to an inoperable lung 18 months prior. I have not eaten since Tuesday. My throat constricted and the flap which directs food, water, and air to the esophagus or lungs does not distinguish among them. "Aspiration", it's termed, as though it's desirable.

Most of the time, I see a path out of here. Maybe it's only the shadow of a suspicion that there ought to be one. Or that willful craftsman I am, I could fashion one. I have the desire, the physical strength, and the support to follow it. Some quality of life for a couple of years still lies ahead on it. If I've miscalculated, I'm still humbled by those who insist on keeping me around long enough for an end zone dance.

Daylight approaches. Mary stretches her legs from under pale blankets, and like Homer's "Rosy Fingered Dawn up from the bed of her sleeping lover Tithonus, goes out to greet the new day". I remember translating these recurrent lines from the Odyssey as a college student. An animate world of rocks, leaves, squirrels, birds and sky—stardust, infused with conscious life. We are such gumbo, no?

Time now to decant the brew. I have daughters advancing. And they seem to be ushering a generation of children ahead of them.

november 6, 2015

October quickening

A heartfelt and humble Thank You from the Torges family to all of you who’ve uplifted us with thoughts and prayers in cards, handwritten letters, emails, and phone calls. And a special acknowledgment to my daughters, who looked after us, and to my loving wife Mary, who insisted on sleeping on the couch beside me for weeks on end, and couldn’t be chased to the comfort of her bed. Such an ordeal as this has to be harder on the caregivers. My role was to lie still and have the people I love take care of me.

I needed it all—the thoughts, the prayers and the family support. Chemo and radiation knocked me flat on my ass beginning the 7th and final week of treatment. They crashed me into my lay-back chair where I was unable for weeks on end to do much beyond sleep, drink volumes of water to flush chemicals, and piss. I lay there with shallow and rapid breaths, like a sparrow that slammed into a plate glass window.

But I'm through the worst and on the mend now. Based upon recent ct scan results, the oncologist informed us that the tumor has shrunken appreciably, that there's no evidence of any new cancer spread anywhere, and that blood analysis reveals near normal levels in all important categories. Scar tissue from the radiation obscures much of the affected lung area, so it's difficult to determine exactly how reduced the tumor is, but another scan before Thanksgiving will determine whether or not I’ll require further chemo treatments. The oncologist thinks maybe may not. To date, we couldn’t have much better news.

My strength is slowly returning, spurred on by my favorite month of the year, October. It contains everything crammed tight, and this year its moderate, breezy days carried seamlessly into November. We still have a few garden tomatoes, but the world is tilting toward bare, hang-on-for-your-life times for all God’s creatures living brave. It’s the month between farewell and hello. “Thank you for the bounty” meets “Shit the bed! Finish up with the firewood and get the tarps in place.”

Sunday I walked to the deer stands I have behind the house. Took all my energy, but I did it. After I rested, I poked around a little in deer sign and saw that a doe family was regularly feeding on red oak acorns nearby, and that rutting bucks had rubbed half a dozen saplings raw.

I can haul myself up into the tree with my safety equipment a little at a time. In fact, I planned to go today. It’s time to be there. Two nights ago, around 10 pm, when I went outside to whiz off the back porch, I stepped into the world of a rutting whitetail buck’s distinct and unmistakeable musk. Completely enveloped and startled me. In that moment of recognition, my head turned slowly, my eyes widened wanting to see through the dark, and I think my fangs stirred. This brazen so-and-so is calling me out, I thought. He’s come to my door step to taunt me, to count coup. “Here I am. Where have you been?”

So yesterday, after I’d gathered a few items in preparation, I found the courage to grab a hunting bow, step outside, and pull back. My fears came true. I couldn’t draw it. I couldn’t even draw it half way. The lightest bow I had, and it may as well have belonged to Odysseus.

But Diminished Dean has plans. Plans to get stronger, yes, but short-term plans to make meat yet this winter. I’ll find my way back there when the circumstance is right. My schemes include how I’ll drag a field-dressed deer carcase to the barn. I’ve figured it all out, including the butchering and the processing. Even though I’m short-breathed and weakened, my resolve is great. So you can turn up the volume on the Frenchman with the piano. You know, the one we’re all variously aware of this time of year, the one playing “Autumn Leaves” in the background of our lives. It won’t affect me. I’m more than a sentimental old man, and much more than a scofflaw.

To round off, I’ll mention a phone call I received last week in the hopes that it makes you laugh as much as it did me. It pointed in another direction from the encouragements I mentioned earlier. Fella calls in a halting, grim voice and asks, "Is this Dean?" "Yes," I reply. "Goodbye," he says, and hangs up.

I still chuckle thinking about it. No doubt he’d be disappointed to learn I'm on the mend. I hope he holds on long enough for the news to reach him.

AUGUST 29, 2015

THROUGH THE TOES DARKLY

“And when at last, with tiny blasts on tinny trumpets, we finally meet the enemy, not only will he be ours, he will be us.” —Walt Kelly, Pogo

I’m not railing, shaking a fist skyward. What am I fighting here? Some invader? Some foreign malevolence? No. Torges has turned on Torges. I’ve met the enemy. So the answer is not all-out war, but peace. I recognize the conflict in me and I’m fixing the problem in my heart, making amends. When I’ve integrated the solution, when I’ve made it part of me, there will be no further need for the cancer because the problem it came to signal won’t exist.

The oncologist told me only 30% of the people with my cancer survive it. I’ve hit smaller targets with consistency. Sometimes even the hair over the heart. I have a keen desire to continue living. After 6 weeks of chemo and radiation, there’s still sparkle in my eye and a skip to my step. Today I mowed grass for several hours and then launched my boat and fished the rest of the afternoon.

I intend to come through this. That’s not a statement of faith. Religion and faith are “can or can’t” propositions, not “will or won’t.” I can’t will myself a belief in magic or will a suspension of natural law. Unlike the supplicant in Psalm 23, I’m not telling you with inspiring rhetoric how I will walk through that Valley, made fearless by an unshakeable faith in The Lord, the Oversoul, The Beneficent Force, the Great Spirit. I’m basing a modest optimism on my understanding. I’m fixing this ailment in the same way one fixes a flat tire, a dull hand saw, a creaky door hinge—by addressing the problem. My bet against the odds is that it can be done.

I remember reading these lines from Moby Dick during my sophomore year in college. Starbuck, first mate, spoke them early in the novel, looking down over the side of the Pequod while sailing on a peaceful ocean. Beautiful, moving, lyrical lines. They popped into mind recently. I remember them exactly: “Loveliness unfathomable, as ever lover saw in his young bride’s eye. Tell me not of thy teeth-tiered sharks and thy kidnapping, cannibal ways. Let faith oust fact. Let fancy oust memory. I look deep down and do believe.”

That’s Starbuck’s version of the 23rd Psalm. But until you stare through toes curled over the abyss, you can only hope what you are going to think or believe, or how you will act.

When Starbuck realized the extent of Ahab’s madness, he had a thought and a chance to murder him. He didn’t. Why, I do not know. If it was for some reason beyond believing that his faith would sustain him through that Dark Valley, then I wasn’t perceptive enough as a callow student to divine it. The time came, though, inevitably, when the sea was not so calm, when he was sucked into the vortex of a smashed and sinking Pequod while the harpoonist Fedallah’s dead body, lashed to the white whale, waved him goodbye. I wonder then what he thought about “loveliness unfathomable" and the averted eye which plunged him into it.

So here I stand at the edge, wanting to sort things out, looking deep, wanting to know where the sharks and the cannibals reside. This morning at dawn, while I lay in bed (a time always of clarity and honesty for me), I composed this simple prayer to my cancer:

Thank you and bless you.

You’ve done your job, accomplished your mission.

You can go now.

AUGUST 16, 2015

TIBET TORGES

I’m doing ok, really. Better than I expected. Beginning the 5th week of chemo and radiation tomorrow, the noticeable effects so far have been less annoying than a summer cold. I still have hair on my head, still weigh in at 180, suffer no nausea, and notice little beyond some indigestion, a difficulty swallowing, and a fall-flat weariness after fishing eight hours. We are fighting a good fight here, and Mary, my stalwart friend and help-mate for 54 years, has never shined more beautifully than now, taking care of me by every consideration.

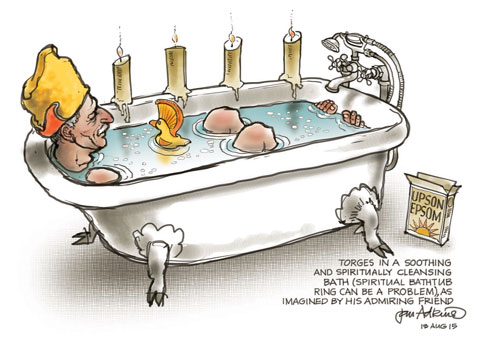

Our daughters Beth and Cindy funnel attention and organic foodstuffs my way, too, and Beth and Mary burn up the web searching out supplemental healing means and resources. Their difficulty lies in sorting through the woo-woo to find information with credentialed research behind it. Mary has me on a regimen of spirulina, wheat grass, and flax seed oil to increase blood oxygenation, juicing of various anti-carcinogenic vegetables, and Epsom Salt body soaks to decrease overall acidity, all this overlaid by a keen awareness of sugar’s effect upon cancer cell growth. Beth recently sent an email cataloging several scientific sources supporting each of these paths. We regard them not as alternative remedies or approaches, but as complements to the regimen of radiation and chemotherapy.

Something must be working. My white blood cell count is up over last week’s, and in all important categories, blood work analysis places me well within the normal range of a healthy adult.

Still, it must be frustrating poring over and sorting through claims and counter claims, the urgency of it all wearisome to my family, though I have no clues suggesting anything but a loving eagerness to go far and search deep. Concern that the toll is greater on Mary than it is on me led me recently to hit upon a diversion. I thought to replace a cat that she loved dearly and lost several years ago with a kitten. Mary sat calmed and relaxed with Pandora on her lap for hours in the evening while she read. Sometimes they fell asleep together there with the book fallen open. And when she played the piano, Pandora would often come walk on the keys. But Mary won’t hear of it, claiming she has no time now, and vows not to care for it. I bluster and threaten a bull rush to the shelter on my own hook to fetch one, protesting that I want one, but she pins me with sharp eyes, reminding me that with my vulnerable immune system, the last place I need to be is stirring around a litter box. I may call her bluff anyway.

Yes, there’s a downside to all this, but the disease also provides its perks. For example, I don’t especially like visitors or even phone calls. I’m a solitary person living a secluded life in the woods, hunting and fishing by myself, with just a tiny love for humanity. But my friends and relatives want to come see me before I die. They’re kind and loving and tell me nice things. I like that enough that I haven’t told them I’m putting off the funeral. In fact, it makes all visits, all conversations, all contacts with people I love more poignant, more honest, less taken for granted. That’s a very good thing indeed.

Also, I’m freer with self-indulgences now. Without second thoughts or so much as a raised eyebrow from Mary, I’ve spent a ton of money on fishing tackle recently, counting a $300 fuel pump repair to my boat’s 9.9 kicker motor, to include two very nice 7 1/2’ rods, a Shimano spinning reel, three hundred dollars worth of lures, and some miscellaneous etcetera stuff such as epoxy powder paints, lines, hooks, snaps and beads.

Within several days of the diagnosis, I purchased a Woods three-point hitch grader blade for the driveway. I’ve wanted one since I got the old Ford 800 tractor, but I’ve continued tending our long gravel driveway by hand, hauling my own stone, and with a mattock, rake, and shovel, making adjustments to grade and pothole. So, just as I rationalized purchasing a log splitter 10-15 years ago, I decided the addition of a heavy duty tractor blade from Craig’s List would make life a little less strenuous these final 20-some years.

The effects of illness have been most noticeable around the property. Nothing much more than preliminary work shows at the new henhouse site. The foundation, laid out with two 7’ by 7’ concrete slabs, lies guarded now by huge growths of elephant ears and pigweed, like some miniature Aztec ruin. That’s ok. The old one still keeps the eggs dry and the hens safe. It’s ok that the garden is a bit of a disaster, too. Besides tilling a trailer load of rotted manure into the tomato patch this spring, I didn’t tend it much. It won’t yield enough from two dozen vines for canning the 50 some quarts we usually require each year. Not much more survived the weeds and neglect than the four kinds of heirloom winter squash I sowed and mulched. Next year I’ll pick up the beat again.

An order of lures should be here tomorrow. I’d like to wait for them, but I’m going fishing before they arrive. We live differently threatened by impending death or lost love. But that’s our actual condition, isn’t it?

July24, 2015

CONTINUING THE JOURNEY

All is well here. A pet scan and another ct scan Monday removed much uncertainty and revealed the cancer seems largely confined to my left lung and nearby lymph nodes, so even though it’s at stage III, it’s not bad news. I began radiation and chemotherapy the next day, to last for seven weeks. Then, reappraisal.

I’ve been on some miserable trips before and gutted them out. Will again this time. I have a new hen house to build and garden tomato virus blights to overcome. Friends and family yet to cook for. Say nothing of the squirrels, fish, deer, rabbits and rainbows to chase. The other miserable trips I pretty much endured by my own resolve. With the love of my family and the support and good wishes of my friends, this won’t be as bad as it’s cracked up to be.

I couldn’t have a more supportive wife than Mary, dedicated and determined to usher me to health. Ours is a working kitchen, and we eat healthy meals. Mary is quite food conscious. We pretty much avoid industrial stuff. I think you might even characterize her as a health food nut, with me somewhat reluctantly in tow. In fact, now that I’m more or less at her mercy, and now that she’s ramped up her consumption of nutritional and spiritual reading material, I’m beginning to fear that the worse of this ordeal may be surviving the food plans she has in store for me.

So chin up. Wish me well as I wish you well. We’ll have time yet ahead of us for more trips, more adventures, and more memories.

July 12, 2015

Oak family

Hello, friends and acquaintances. I found out recently I have inoperable lung cancer. Will begin radiation and chemotherapy sometime next week. Was stunned and thought I’d had the death sentence read to me the evening the dr. reviewed the ct scan, but by morning I decided I’d stay around a while longer. Let’s hope I’ve made a wise and effective decision.

We host the Torges and Ramser family reunions here, and I’d been looking forward to refining my pig-roasting skills, but we’ve canceled plans for this year. Later on, we’ll all get together for one helluva bash.

I have a confident, positive attitude about this. It’s not bravado. Like dealing with a lawnmower engine that should but won’t start, or a garden pest in the green beans, these are not the kinds of aggravations you shake your fist at; instead, they are part of the daily business of dealing with life.

And so in that spirit, I want to fwd to you a mail that I sent to our families after I’d canceled the reunions. I hope they found it some comfort. I hope you do, too.

We have a huge white oak comprised of 5 trunks just to the west of the house. It’s the signature tree on our property and was well-established when we moved here with our young family 45 years ago. Lightning hit it hard early this spring, tearing a gash down the lead leaning furthest from the house. It also traveled across to the lead leaning over the house via a steel cable tying the two together, peeling bark off it all the way to the ground. Mary and I were watching a movie at the time. It seemed to lift the house off the foundation, filling it with a blinding white light. Fried the flat screen, our telephones, the computer modem, the satellite dish, and some other stuff.

The whole upper story of the tree had been bolted and cabled together in a mutual support system as a precaution against calamity. But now the lead leaning away was fractured and the bolt blown loose. Its mate, previously held in equilibrium by the cable, shared the blow and was left leaning dangerously over the house.

The first arborist I called tried cabling them back together, but there wasn’t sufficient good wood left for a bolt to hold on the outside lead. He suggested pruning them back significantly. A second arborist suggested placing a newly-developed sling system around them and re-tying them with cable, then waiting to see if the leads budded out. If either died, it and the one tied to it could then be reconsidered.

We did the latter. And a good thing. Oak family survived, leafing out on schedule. The five trunks, sharing a common root system, were able to absorb the blow. They’ll last a while longer. I like to think about it.

December 22, 2013

A word from my altar ego, Rev. Roy Gracklin

I support Phil Robertson 100%, although I would have preferred that he just said he was against homosexuality because the third book of the Bible, Leviticus, Chapter 20, verse 13, condemns it. He shouldn't have said that a woman's vagina has more to offer a man than another man's anus does, because really we're not talking preferences here, we're talking about God's law. That kinda turned some folks off who might otherwise have been ok with him simply stating homosexuality was against his scripture-based beliefs.

There are other equally important prohibitions in Leviticus. I hate it because I was a fan, but it looks like the Beatles are hell bound, too. Leviticus 19:27 reads "Ye shall not round the corners of your heads, neither shalt thou mar the corners of thy beard." Mop haircut is a no-no. And notice how completely Phil and his sons obey this stricture. No mop haircuts, no trimming of the beard. Excellent.

I'm thinking he might have had a little trouble with Leviticus 11:8, though. It prohibits eating pigmeat or touching anything porcine as an abomination, so bbq, bacon, and a fistful of cracklins are out. Perhaps Phil insisted on rubber footballs for the pigskin as a college quarterback to get around this, I don't know.

Chapter 11, verses 9-12, state that anything in the rivers or seas that doesn't have fins and scales is an abomination to the Lord, and it's flesh must be avoided. I can't speak for Phil, but I've been sinful and need to turn away from clams, shrimp and lobster, among other things, and do without crawfish in my gumbo, boils or etouffee. Oysters, too.

I have an easier time not eating camels, owls, hawks, cormorants, buzzards, osprey and eagles (illegal, too), grasshoppers, locusts, bats, storks and pelicans, among other things (such as snails, moles, lizards and chameleons). These are all listed as abominations just as certainly as homosexuality is. I only wish Leviticus had included more critters like these and sorta given a pass on the crawfish and the shrimp. It wouldn't be so hard to obey God.

But it's not supposed to be easy. Maybe that's why Leviticus proclaims that eating the flesh of rabbits is also an abomination to God. I guess we're all sinners, aren't we? It's tough being God's servant. None of us is perfect.

Now one thing I don't have trouble with is tatoos. Leviticus 19:28 prohibits tatoos. I don't have 'em and I'll bet none of the Robertsons have 'em, either.

It's also a good thing they are not farmers, because the Bible prohibits the crossing of cattle, such as Angus and Hereford, and it also expressly forbids planting two kinds of seed in an agricultural field. That's Leviticus 19:19. It must be easier to be holy if you aren't a farmer.

I'm not second-guessing the Good Book, by no means, but I think God would give us a pass nowadays on the prohibition against wearing garments made of two different kinds of fabric. I don't think Leviticus knew about the virtues of rayon and cotton blends, and I'm betting wicking away body moisture would get polyester and nylon in the duck blind a dispensation, too. But I could be wrong because God according to Leviticus works in mysterious ways.

Or at least our interpretations of his Word and Will sometimes seem mysterious. I have a gay nephew. He's a dear boy. Absolutely harmless and decent. Treats everyone with respect. Doesn't know how to lie, cheat or steal. Been with the same partner for maybe 10 years or more. Wouldn't ever commit adultery, not because according to Leviticus 20:10, he and the adulteress should be put to death if they did, but because, ah, well, just because. I'm hoping he gets credit for that.

----------

"You can tell you've created God in your own image when it turns out that God hates all the same people you do." -- Anne Lamott

February 7, 2012

All You need to know

Men, I'd like to take you aside for a tête-à-tête. Let's leave the women behind for the moment. This is not for them. It's about them, ok?

After fifty years of marriage, I have wisdom to offer about living peacefully with the opposite sex. Actually, my experience with women runs even longer and deeper than that. I was reared by my widowed mother and three sisters 15 years and more my senior. And I fathered four daughters. They in turn birthed four granddaughters before Varmint was born 8 years ago to our youngest daughter. In fact, before Varmint broke through, our cat and dog were female, too.

Some may consider mine a lonely experience, or me a survivor under lifelong siege, while others might envy my station, wishing they had lived attended by nourishing women from every direction softening their path through life. Regardless, everyone should agree that I qualify as a spokesman for partnering with the gentle people on the other side of the sexual barrier.

I accept the responsibility, but with qualification. I should know more about everything, not just women. This attitude is shaped by my impatience to learn and tempered by the realization that this long into the run, it's likely I won't get much further. I'm resigned, but unsurrendered.

I've always puzzled over women, recently with renewed effort both because of our 50th wedding anniversary and also because we just completed purchase of a new living room outfit—chairs, couch, console, end tables, mirror, pillows and various accoutrements.

You may not consider these events equally powerful to stimulate reflection. They aren't. Our anniversary was spent as a quiet day at home, while the living room purchase required on my part no less than five separate trips to Columbus furniture stores followed by four separate four-hour round-trip drives to Sugar Creek, Ohio, once Mary's selections had narrowed. That's one day of peaceful relaxation weighed against at least ten days spent wandering through furniture store mazes during 'coon, squirrel and deer season.

But what I've learned I'll share. Don't dismiss the lesson because of its simplicity. It may well be all you need to know, too. After all, I've got myself this far by it. And don't be disappointed because I don't offer you insights like women have. I'm offering instead codes for behavior. I learned them early in life, and though I should probably know more, I've found neither reason nor capacity to expand upon them. Indeed, their simplicity increases their value during the duress of crunch time.

1. Make a decision.

2. Live with your mistake.

3. Don't complain.

Upon examination, the more perceptive among you will conclude them redundant, that any one of the three is just another way of rephrasing the other two. You would be correct—they are indeed different ways of saying the same thing in that one implies the other two. Not complaining means you've made a mistake and are reconciled to it. Or, looking through a different knothole, living with your mistake means accepting it, not complaining. And so forth.

The value in seeing this dynamic from three perspectives lies in the likelihood that at least one of them will resonate, and the truth of three iterations is that on matters of behavior, men often need reminding more than twice.

These are codes for behavior, not insights into behavior. Men require codes. Women desire insight. These two diverse needs explain why we're constantly puzzling over each other. "What does she want me to do?" meets "Why is he doing that?"

I see shapes. Mary sees colors. I see proportions. Mary sees thirty shades of beige. Because her nuances don't exist for me hardly means they don't affect my world. If she wants to ferry colored fabric swatches back and forth between Ostrander, Columbus and Sugar Creek, to arrange them against drapes, carpet, bricks and walls, in daylight, low light and under artificial light, should I do less than marvel at her tenacity and determination? Aren't those qualities I admire? Should I tell her to make a decision and live with her mistake? No, dummy. These rules are for you and me, and they nowhere suggest we should avoid what is inconvenient to us. Instead, they tell us how to deal with the inevitability of inconvenience. You made your decision. Don't complain. It would be a mistake.

It follows, then, that full disclosure in a marriage is much overrated. There are things you can tell yourself and your God, but no one else. That's not deception. It's politics. Besides, unspoken truth always affects your behavior, and your behavior always reveals you to your spouse.

For example, while driving to Sugar Creek yesterday along winding country roads, I turned my head slightly to notice a solitary woman walking the berm in the middle of nowhere. Moments passed before Mary inquired, looking straight ahead all the while, "Was she pretty?" Should I have confessed sometime early in our marriage that I like to look at pretty women, or that I like to look at all women, and probably always will? Or should I have said, "Sorry. I was trying to sneak a look." Or should I have lied? "I dunno 'bout pretty. I was wondering what she could be doing out here."

I answered, "Not really." Why? Because the rules rescued me. I thought a discreet glance would go unnoticed. Bad decision. #2 directed me to answer her question directly, to focus exclusively on the situation, own it, and get on with life. Getting on with life after you make a mistake is the first corollary of Rule #3, Don't complain. In other words, don't defend yourself, don't try to explain, don't dwell on the past, don't get complex or metaphysical. No one wants to hear it, and you risk confusing yourself. Besides, she already knows the truth.

That was the end of it. Mary was satisfied. I understood by her question and demeanor that she anticipated my behavior, that she knew I was bound to look. She also knew my answer acknowledged the subtext of her question. Result? Harmony. Politics as it should be practiced.

Women see and know, and therein lies their power. Of course, I'm not talking about which end of a bolt the lock washer belongs on. I'm referring to relationships. If they don't know, they soon will. This is their truth. In fact, it is The Truth, of such overreaching magnitude, that it is The Truth whether it is or not. And if you think about this, you'll understand why it's very important that you live by numbers 1, 2, and 3.

January 6-12, 2012

Fill 'Er Up

It's a joy hunting with Digger and Tricks. Digger courses the woods at a steady lope, fanning back and forth, inquiring. He's a young man's dog in that he'll find game somewhere and do it post-haste. I admire his energy and enthusiasm while I groan to keep up. Tricks has matured into a strong tree dog with an independent mind. She takes life at a slower pace, but she can hold her own with Digger for treeing game. Both show in abundance the gritty determination, brains and the desire to please characteristic of the Mountain Cur breed.

The three of us took another bag limit this Thursday, two days ago. Counting these six, I've dressed and stockpiled enough in the freezer to make about 24 pints when I get around to pressure canning them. I've given away many more than that, but 24 pints is plenty for us.

The day before, on the spur of a good walleye report, Young Jamie and I planned to head for Lake Erie. Mike Justice and Kevin Toms told us that fish were off the Huron River, about two miles out. But night-before second thoughts over a hastily planned 4 a.m. drive made a local inland lake an attractive alternative.

The O'Shaughnessy Dam holds a good population of saugeye, and a stretch of open water circling my honey hole promised a bonanza. It was framed by frozen water in both directions over the remainder of the reservoir, so we sorta went ice fishing, breaking through 3/4 to 1 inch of ice at low speed for about two miles from the launch site to get there.

The water temp along this shallow shelf, with deeper water surrounding it, was four degrees warmer than the rest of the iced-over lake. Schools of shad, attracted to the warmth, dimpled its surface. Saugeye favor this forage fish, and on some mysterious cue will move into these schools from all directions. It's like a set table for them.

Everything seemed in our favor except for the water clarity itself, which was heavily stained from previous rains. We gave it a long and thorough effort, thinking to counter the water condition by trying this and that, jigging vibrating blade baits, casting lures with rattle chambers on a slow retrieve, varying retrieves, even trolling. Maybe we got there before the saugeye arrived, maybe we got there too late. We should have caught fish, but none came on board. Still, it's comfort and incentive to know that on the next try, we won't do worse.

The day before that, Tuesday, Young Jamie and I squirrel hunted. The dogs were on fire and game was moving. Our first ten squirrels came fast, but two squirrels short of our Ohio bag limit, a steady drizzling rain set in, scattering game. We got ourselves thoroughly wet before Digger and Tricks found numbers 11 and 12.

Monday evening, Jason Fairchild brought his young female Mt. Cur over for her 3rd coon hunt. Tilly is out of a littermate sister to Digger. She lacks his motor, but otherwise shows great promise. The coon were moving well and Digger and Tricks performed at their usual high level.

Saturday morning my nephew George came down from Stow to keep me company deer hunting for the weekend at the Mouse Palace, the little cabin/camp in the game-rich hills south of Athens. We killed a doe each day. What with the squirrels, the fish and the chickens, there'll be meat to share until next winter.

Friday marked our 50th wedding anniversary. Mary and I stayed home and enjoyed each other's company, reminiscing over one of our favoirite activities—preparing a meal together in our kitchen.

Several days before, while searching through a document containing website usernames and passwords, I saw that Mary had answered "Dean" to the prompt question "Name of childhood friend?" We met when we were 20, but some truths transcend facts. This one made me laugh.

Cold winds and snow blew in yesterday providing time to stoke the fire, crouch on a low stool beside the stove with hot, fresh coffee, and draw upon time spent these past seven days making memories.

September 23, 2011

Farewell to the Ash Tree

The Emerald Ash Borer is upon us, and soon the landscape will be as barren of ash as it is of American Chestnut. Probably one third of the mature trees on our property are white ash. Twenty-one large ash trees rim the yard: along the driveway, by the house, behind the woodshed, beside the henhouse and in back of the pole barn, and more struggle deeper in the woods. They leaved out at about 25 percent this spring, their vital fluids drained by the borer. I look toward them often, to their spare branches thrust up through a lush green sea of oak, walnut, maple and hickory tops. They look like the outstretched fingers of a drowning victim going down.

Their departure here and nationwide would break my heart if I didn't view it in the context of a life that's seen dramatic changes headline its many chapters. As such, there's just sadness sufficient to mourn yet another irretrievable loss. I'll be cutting them down these next two winters. The butt logs will saw into boards that I'll stockpile, and the top logs and the bigger slash will become firewood. Brushpiles for the balance, sanctuary for birds and small animals.

In anticipation of filling the woodshed and crowding out the tools I store there, I built an add-on toolshed during the various intervals of pole barn construction. The log splitter, the chain saws, mauls, chains, ropes, cables, cant hook, carts, and misc. other tools required their own nearby storage shelter, and though the roof height of the woodshed did not lend itself to a build-on, I didn't have much choice but to lower my head and do it.

This is pole barn construction again, with random width vertical board on board siding. Since the boards run narrow, I nailed them as I would batten and board construction, lapping them one over another by about an inch to each edge, and then putting a galvanized nail through the middle of each board into the stringer behind it. No two boards are nailed together; each is free to expand and contract from its center, independently, without splitting at the nail.

September 10, 2011

Nailing It

If I had no other interests, it'd please me to construct buildings all over the property. Tool sheds, hen houses, smoke houses, playhouses, dog kennels, machine sheds, butchering sheds, hot houses, tree houses, and more tool sheds. Stone buildings, brick buildings, pole buildings, and log buildings. I'd go to the back of the woods and build a cottage just for writing novels and poetry, and then maybe nail up a shed-roof addition for carving fishing lures, making tackle and wrapping rods. If I never intended to write or fish again, or put any of these other buildings to their purpose, I'd still build them.

Regardless of type, their parts assemble to the sound of the hammer at work. Drive 20d galvanized ring shanks and bury them. Position another spike. Bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, BANG! down the scale until with a final wallop the hammer face stamps a neat seal around the countersunk head, notarizing the marriage of iron and wood. Done in rhythm, again, and again, the framing hammer rings like a tom-tom to my generation, reaching across neighborhoods, suburbs, and farmlands.

I've built 6 structures on our property that qualify as pole buildings, ranging in size from an 8x10 garden shed on the other side of the pond to a 24x32 hip roof around an existing tool shed, and I have two more planned for next year. Dig postholes, drop in the poles, plumb them as you back-fill, throw trusses atop them, and skin them over with your choice of siding and roofing material. Simple, elementary.

None has been so large that it required the help of others. This pole building changed that, and I couldn't have hired a better local framer than Mike Grandominico to carry the load. Goat footed, barrel chested, and sharp as a 9 point ripsaw fresh from the filing vise, he can heave it, swing it, and nail it. We've teamed to do the bulk of the work, but the job of hoisting the attic trusses onto the girders required additional help.

We discussed several approaches. Mike voted to save money by using the skid loader, but I opted to play it safe. At the rate of $350 dollars for the first two hours, beginning when Willie's Crane Service left the yard, and 100 each additional thereafter, Willie agreed to hire out on a Sunday morning. Yeah, a bunch of money, but then the attic trusses came to almost $3,000.

The day before, Mike framed up 2x6 stations on the girders to register truss position so we could work quickly and efficiently. Figuring to keep under the two-hour cap, we rounded up a few friends, and at daylight everything came together. From the time Willie positioned and fired up the boom crane to when he lifted the gable peaks onto the upright trusses, barely an hour passed. Even considering travel time from nearby Radnor, it went so well that Willie only charged me $250, plus a package of walleye fillets and a frozen broiler.

After the trusses are up and the purlins on, it's wham-bam with the tin skin. Mike is a workhorse, competent at every facet of building. There's a time for rough work and a time for finesse. Some folks can't distinguish between the two. Some can't do both. Mike can, and at warp speed, too.

Much of pole barn building is two-fisted, five pound hammer stuff. Mike and I teamed well. When the work required us to go separate ways, I claimed the small hammer and Mike grabbed the one that went with the anvil. While he was nailing on purlins and cutting tin or dancing on steep ledges, I stick-framed the gable walls (one for a large window, and the other for a "hay-loft" door) and built the stair case.

Most folks climb stairs with no understanding of their rhythmic grace. Finish carpenters are charged with keeping them safe while they sleep. The dynamics of stair travel have us calculate step height from the first few steps, and we do this so reflexively that we're off thinking other thoughts while we climb. If there's a deviation after we get rolling, the risk of tripping or falling is great. Therefore, laying out the stair stringers correctly is a great responsibility.

With this responsibility come algebra calculations to anesthetize the brain. It's as though a unique staircase to fit each situation exists in the ideal world, and the finish carpenter is charged with finding it and making it real.

The bottom riser must be shorter than all the others by the thickness of the tread, and the top riser must be the height of all the others, including the tread, but minus the thickness of the finished floor and subfloor. For comfort, all of them should rise around 7 inches. The runs should be close to 11". These restrictions are constrained even further by the height between floors and the length of the total run, which vary with each circumstance, and which in combination determine the total number of risers and runs. Once these legs of this right-angle triangle are established, the total rise and the total run factor into the equation to yield the precise and uniform dimension of the individual riser and its run. It may be simpler than this, but not as I understand it.

Whether you're building a bare-bones, dimensional-lumber, straight-up-and-down staircase like mine, or a winding, elegant one of hardwoods, tapered in tread width from top to bottom, with fanciful newels and spindles, the only room for variation or artistic expression in this process lies within the borders of these formulae, which are as unbending as the rhyme and meter patterns of a Petrarchan sonnet, and just as satisfying when beautifully met.

My humble variation on this utilitarian staircase consisted of accommodating the concrete floor. Since it sloped at the rate of 1 inch every 12 feet, and since the stairs ran against the slope, I accounted for the difference across a 3.5' span of stringers by making the second or middle stringer 3/16" higher on the first riser alone, and the third or outside stringer an additional 3/16" higher, for a total of 3/8" difference. The consequence was a level tread left to right as well as front to back. Not something you would know or appreciate while climbing the stairs, but by my estimation something still worth doing.

. . . . .

Mike had to leave for a wedding in North Carolina yesterday before we could screw the last piece of tin in place. I occupied myself cleaning up the site and sweeping. Just as I finished the south bay, Mary drove up, home from the grocery store. I waved her in and we both laughed 3rd grade over our very first garaged vehicle. I finished cleaning the middle bay, and then pulled my boat out of the shop and into its new digs, in the process reclaiming the shop for furniture and bow-building. Glorioso.

The overhead doors come next week. I'm paying to have them installed. There are a few more storage shelves to build, some shovel-grading around the foundation, and a few small projects to finish, such as doors for the tool-shed addition to the woodshed. Otherwise it's a wrap on the summer. Time now to hunt and fish carefree.

August 18, 2011

Memo to Alfie

"The caterpillar on the leaf

Reminds thee of thy mother's grief." —William Blake

We have central heating, but we've burnt wood for heat almost since we moved here 44 years ago, when fossil fuel was cheap and the house was uninsulated.

We started modestly, supplementing the oil furnace with a fireplace that probably sucked out as much heat when the coals died down as otherwise radiated into the living room. From there to an ancient potbelly, through several used Ashleys in succession, and then on to airtights. Though we investigated installing an outdoor wood furnace with a catalytic converter and a hot water system several years ago, we stopped short of it.

I traded the potbelly for a fox terrier pup, and probably just in time, too. A neighbor gave us the stove, a beautiful, ornate relic with detachable chromed skirts for use as bed warmers. I carried it in sections to the basement because it was too tall to vent into the fireplace, troweled asbestos cement into the ill-fitting parts of the firebox while reassembling it, teed it into the furnace pipe, and cut a hole above it in the living room floor which I fit with an old cold air return register so the heat could rise upstairs. I didn't expect much, and I didn't get much, either. If the stove had heated the upstairs a noticeable amount, if fires had lasted longer in it, if it weren't such a burden to carry firewood down to it and ashes back out—if there had been fewer objections to its regular use through a cobbled and inadequate vent—the story likely would have ended with the house burnt down.

We rebuilt the fireplace with old brick when we added a two-room addition 20 years ago. Well before that, a creosote fire raged through it one night while I was away hunting, and Mary took the children outside for fear the house would go with it. I'd fabricated a steel insert to fit into the face of the fireplace, cut a 6" dia. hole in it, and vented an Ashley through it, stubbing it off just inside the insert. Same sort of thinking that sawed a hole in the living room.

The smoke cooled behind the insert and condensed into creosote, accumulating until it caught fire. Mary said the inferno roared through the chimney like a jet engine exhaust, and she could hear what proved to be the flue liner explode and crash down in chunks. It sent a spectrum of sparks and glowing fireballs arcing into the night like tracers from a sputtering cannon. For some reason they failed to catch the roof afire. The repair consisted of steel stove pipe run up through the flue until years later we rebuilt the chimney with handmade brick that I gathered from a tumbled-down 19th century farmhouse.

According to his descendants, who gave me permission to salvage the site, a pig farmer made the brick in a crude cooperative neighborhood oven during the intermissions afforded by a 5 to 9 workday. The clay was of uneven quality and of several hues, and the oven must have been hit and miss as well. Some bricks came soft and weathered quickly while others still remain rock solid. Colored mineral stripes run through some, all vary in size and shape, and you can see handprints of fingers and thumbs in many of them, further evidence that they were cut roughly and handled hurriedly before they were fired. Their story reflects through them.

I dug them out from a layer of snow, brought what I needed home in the middle of winter, chipped off any mortar that clung to them, and set them to dry on the floor of the room addition. From there with the help of two friends we layed them up around and over an archway that joins two sections of the house and affords heat to both.

. . . . .

The act of cutting a season's worth of firewood a year or two ahead of need anticipates hard times. An urgency therefore attends it, but since the woodpile becomes a fortification, it's calming, too—a stick at a time becomes one night's warmth per arm-load stacked. Eight cords of firewood, a winter's burn ricked up under roof to cure, will make the man who toiled after it stand back and smile. You don't know the same winter by writing checks for fuel and hurrying past an electric meter bolted to the side of your house. You can't feel the same about life, either.

Until 2003 and the purchase of a gasoline powered hydraulic wedge, I split rounds by hand with mauls, axes, wedges and sledges. There were crotches and other burly woods that beat me down, and bucked rounds I turned my back to in the woods because I knew I couldn't split them. Hydraulics leave nothing behind. Now, everything goes to the woodpile. In 2006 I built a 14x20 woodshed near the house, and we've had the luxury of burning easily accessed, dry wood since. I could have made both moves much earlier, but I didn't.

For most of these years laying up and burning wood made no economic sense, but that was never a reason not to do it. We've dried clothes beside our stoves, cooked on them, humidified the house with them, and huddled near them to thaw out fingers and toes. We've piled on the blankets in chilly bedrooms, too, where their warmth couldn't reach, and on the coldest mornings we crowded around a radiant heat source once the banked coals kindled into new fire. Just as there's more to the geometry of laying logs in a stove before bedtime than a careless or inexperienced man might think, there's more satisfaction to be found in the firewood process than what shows on balance sheets.

Money has never influenced an important decision for me. By that I mean I never chose a less alluring path over another because of the dollar bills at the end of it. Instead, my energies have gone to following curiosities and passions. I realized early on that if money is used to buy lavish passage through the world, or to compensate drudgery with toys and a family vacation each summer, then money costs too much.

My father-in-law was a practical man. He left the family farm as a youngster and became a coal miner. His was a generation hired to make bricks for other people while it dreamed of a better life for its children. To that end, he pushed his sons toward the Dream. One became an orthopedic surgeon of some renown. Another a Harvard grad, a lawyer and Vice President at Wheeling Steel. A third an engineer and a Vice President of Alcoa, with many credited patents from NASA's space program. The fourth an engineer/entrepreneur who founded the Ohio Cumberland Gas Company. He left Mary and me to our path, and we chased a different dream. Now and then he suggested we'd be money ahead buying beef rather than raising Holstein steer calves, or that store cheese was cheaper and less bother than homemade goat cheese. I couldn't argue.

But the question for me was never the time-and-money cost of a venison backstrap, or a pound of fish fillets, or a grass-fed broiler. My goal has been their pursuit, and money exists to facilitate their pursuit, not to circumvent it.

I'm no survivalist or doomer preparing for economic catastrophe, political chaos, or famine, pestilence and biblical horror, at least no more so than for international peace and prosperity. I'm an entry-level participant in life, here to experience the excitement and the satisfaction these simple, elemental pursuits provide.

In the pursuits lie the rewards, and behind them the passion that fuels the heart. In their wake and from the fire of that oven come soil to nourish cukes and zucchinis, tapered wooden shingles on a hen house roof, osage bows nocked with straight arrows, egg yolks that stand up proud, jars of canned squirrel, and ricks of cord wood, tall and stable. Their story reflects through them.

July 17, 2011

Hen with Rock-Cornish Chicks

I cut short my fishing trip with Mike to Lake Erie to stop by Eagle's Nest Poultry on the way home and pick up 20 newly hatched broiler chicks. Hated doing it because we'd just an hour before lifting anchor found were the perch were schooled, and though the fish ran small, from 8 to 10 inches, the action was non-stop. But I had to get to Eagle's Nest in Oceola before closing time.

The easiest way to raise chicks is to put them under a broody hen and let her do the work—usher them about, find food for them and keep them warm and away from harm. I've done it with three hens so far this year.

When a hen goes broody, I'll place two eggs under her and isolate her from the flock. After three weeks, just at dark, I'll push about 20 day-old chicks under her. She thinks she hatched them, and they imprint on her. The next morning she's off the nest with her new brood, full of mother-hen business. WHile she can only hatch 12 to 14 eggs, covering them sufficiently to brood them, she can care for many more, especially in the summer when the nights are warm.

We still have 75 red broilers ordered for August, and will raise them up in the Coop de'Ville with brooder lamps.

July 13-15, 2011

Pouring the Floor

After the posts were set, Brad sent over Josh and Jarrod to prepare a base for the concrete floor.

Despite the clay that Chaz packed in, in order to bring the base up to grade for a 4" concrete floor, we still required two tandem-axle truckloads of 1's and 2's, (Ohio Dept. of Transportation language for washed, fist-sized limestone rocks), one load of 304's to cap them, and two loads of 57's, half of which we spread in the parking lot ahead of the pole barn.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Josh would put down a thin layer of each kind of rock, spreading it with the front end loader, and Jarrod would come behind, rake it out and then settle it into place with a plate compactor. The "three-oh-fours" had limestone dust in them to form a crust over the fist-sized "ones-and-twos." Josh wet them down good with a hose so they would settle in.

After a lunch of deep fried perch and walleye fillets with French fries and cole slaw, the men laid down a thick plastic vapor barrier, cut and put down the wire mesh over that, graded the slope around the outside of the building and helped re-plumb and re-brace the posts that required it.

|

|

|

|

|

The next morning, Brad's crew was on site at 6:30 a.m. and the first of two concrete trucks arrived shortly thereafter. This crew has been together for a bunch of years now. They form a solid team and they're very good at what they do.

July 11, 2011

Mary Won't Go

Mary won't go into the basement anymore. But what if she needs a jar of tomatoes? It's my job to go after them. Lettuce or bacon or something from the extra fridge down there? She sends me. Fish or chicken from one of the freezers? My job. If I'm not here and she needs basement goods, I'll get here eventually.

Oh, she's quite capable of climbing stairs up and down, of carrying three or four packages or jars at once, but she won't do it, won't go after them. It's my fault, too. I should have known better.

I forget now what reason took us there several weeks ago. She saw a snake on the floor near some boxes and pointed it out, a harmless five or six inch baby garter snake. It didn't seem to bother her. She's seen snakes in the yard without reacting emotionally. I acknowledged it and went about my business, leaving her to hers and it to its.

I happened upon the snake again days later while fetching a jar of canned goods. I brought it up and showed it to her. She watched as I pitched it into the woods. She heard the epithets and warnings I sent after it. She heard me declare the basement a snake free zone, and if I threw in a fist pump for the visuals, she saw that, too.

But it all made no difference. Mary won't go into the basement anymore, it's my fault, and I think she likes it that way.

July 9-10, 2011

Setting Posts

After Chaz compacted the clay, Mike Grandominico came by of a morning and we laid out the pole positions. Mike is fully occupied at the moment cutting wheat and baling straw, and is only available for a few hours in the morning before the dew comes off.

But when Mike Justus was able to bring his Bobcat over several days later and help out, Mike G. took time off the baler to set posts.

We used an 18" auger to drill holes. Hindsight says when Mike J. asked, I should have requested his 24" auger. We wouldn't have had to chisel off the corners of the solid cement blocks we dropped into the holes for the posts to rest upon, and their alignment would have been easier.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

July 8, 2011

Third Thoughts

Been fishing in Lake Erie these past several days. Went to bed past midnight last night, and jumped up at 5:00 this Friday morning to try a local inland lake. Unfortunately, a thunderstorm started up at twilight just as I began sliding the boat from under roof. I should have checked the weather radar before going to bed last night. That's ok, I thought to myself, I had other things to do, likely requiring a full day, in preparation for Mike Justus and Mike Grandominico coming early tomorrow for us to begin drilling holes and setting the 30 some posts required for the pole barn.

We're nearing our 50th anniversary, Mary and I, and all the preceding is to say that despite an awareness of diminished physical capabilities, I feel ok at 70, don't take pills or meds, and still keep up a pace.

So when Mary expressed concern over what she perceived as an increased level of forgetfulness on my part, and told me that problems addressed in their early stages can be slowed significantly, I agreed without too much resistance to visit our family doctor, more to put her mind at ease than to quiet any anxieties of my own.

It didn't help my argument against going when the doctor questioned why we were there and I answered that Mary thought I had sleep apnea. She does, but she was quick to remind me that memory loss was the real reason for the visit. Apnea came to mind, I explained, because I remembered hearing her express concern over that, too.

This is small town America. We know our family doctor almost as well as we know Brad and both Mikes, and Chaz, who packed in the clay for the barn foundation. We all go way back. We know and trust one another, and we help one another. I even pay tribute to the notion of the small town family practitioner who gets paid off in barter goods by dropping off a dressed chicken now and then at Doctor Hickman's office. The nurses get a kick out of it, I ham it up, and Doc does appreciate a farm-raised broiler.

After some chicken talk and a few miscellaneous yucks, Doc got down to the business of forgetfulness. Mary cited instances to back up her concerns. But I countered that I'd always had a reputation for being absent-minded, and the same sort of examples she mentioned only annoyed rather than alarmed others when I was younger. My explanation for their increased frequency rested on two other developments, which I spun into a theory as we sat talking: A. My hearing had diminished considerably over the years; and, B. I tended to consider it a blessing.

Most of the talk that people engage in does not require a response beyond a smile and a nod, which I'd rather gladly give than ask people to repeat themselves. I shared that insight with the doctor, and he nodded and smiled. But, I added, occasionally someone slips in important instructions or information, and an ignorant response can be costly. That sort of situation has increased with hearing loss. I try to concentrate, but the times I don't hear (normal for my condition) have combined with the times I quit paying attention (normal for most men).

Moreover, the hearing loss is aggravated by tinnitus, which I discovered with Mary's help and which I've also come to consider a blessing. We were lying in bed at night prior to sleep; it was still, and the windows were open. She commented on the bullfrogs from the pond, and how she loved hearing their music. I strained but could not hear them. Instead, I countered to her how musical and active the crickets were. She lay quiet for a while and then said, "I don't hear any crickets." So now I carry background cricket music with me everywhere I go, even through winter, and it helps me screed off the human hum. Yes, B., a blessing.

Doc agreed with me that hearing loss could be the culprit. Nevertheless, he had a standard, simple, base-line test of 20-some questions. He'd ask them again in 6 mos. or so. They were easy questions, no tricks, and he'd write down my answers. "What is today's date?" Ordinarily I wouldn't know the answer to that question, even if it were asked of me 40 years ago, but since the day before had been the 4th of July, the answer came easily. "What county is this?" Etc.

When he asked me to spell "world" backwards, and when I spelled it "l-a-r-u-r," I failed the hearing part of the test and unwittingly added credibility to my own theory.

The "Tempest" is probably Shakespeare's last complete play. In its final act, after Prospero has solved all his problems, forgiven those who wronged him, and set everything in order, he plans henceforth to "… retire me to my Milan, where, Every third thought shall be my grave." I understood as a young man the piquancy that would attach to the smallest activity filtered through such a resolve even though I was not yet able to experience it myself, especially since forgiving my enemies seemed a requirement to the equation. Now I can. Now I do.

But I don't turn every third thought into making peace with the grave, with reconciling, in Prospero's words, to the understanding that:

We are such stuff

as dreams are made on, and our little life

is rounded with a sleep. (IV,i,156)

True enough, but my primary concern is to hunt out this little life, grab it up and squeeze from it all the juice it wants to give. The third thought provides background music, cricket chatter, to this more urgent business. I'm always aware of the music at some level, and it chides me to quicken the pace, to learn what I need to know about the nuts and bolts, and the dirt, blood and guts of life; to build buildings, split firewood, catch fish, hunt rabbits and squirrels, pigs and deer and mushrooms; to work on engines, grow garden, wire circuits, cook dinner, make fishing tackle, shoot arrows, tiller bows, cut dovetails by hand tighter than they can be measured, dig holes, build rifles, and curse when my thumb turns blue. To eat a lot of peaches, and with Mary watch grandchildren grow. To learn where everything lives without middlemen doing my work or talking to God for me. To dream a better dream.

So, projecting 6 months ahead, how shall I spell "world" backwards? If I spell it as though I hear "rural," then nothing will have changed. I won't have deteriorated, correct? But if I spell it as "world," I'll have improved to some degree, don't you think? Right now, if I can remember the plan, just to mess with them a little, I think I'll put on a thoughtful face and spell it as "blackbird."

July 6, 2011

Erie Walleye

Mike Justus and I fished walleye today. We landed on top of them, twenty some miles north of our launch, in Canadian water, and had three in the boat before we had all our rods deployed. They were good fish, too, and the twelve that we kept weighed between four and eight lbs. We returned five to the water weighing four pounds or less, and lost one good one at the net, guesstimated at seven lbs.

It's been a strange Spring, what with all the rainfall, muddy water, and the various weather fronts moving through. Fishing inland lakes has been disapointing, and Lake Erie fishing never found high gear after the stained water cleared up. The walleye vacated the Western Basin early, and it's hit and miss to the East. The only quality fishing available to us is North in the vicinity of Pelee Island, where the water runs 4 to 6 degrees cooler. That's where we were, and there wasn't another boat in sight.

June 27-30, 2011

Giddy-up

Pole barn construction switched to the fast track after the hickory came down. Brad Kelley, a long-time friend with a construction company, was able to free up Josh Lowe for some Bobcat work. You may remember Josh's dad Glenn Lowe, the maple syrup man. We staked out the structure and I got a good eyeball on the actual situation in relation to the shop and standing trees. I decided to move things north a few more feet and turn the barn slightly on its axis, thereby providing space to drive the truck or tractor between the barn and shop corners, if need be.

This meant dropping a tall walnut and a big honey locust that interfered with the change, and also grinding the stumps before Josh left with the Bobcat. To further add to the urgency, Chaz Kaiser was digging ponds nearby, and this meant he had fill available for a sub-base. He informed me he was just now getting below the blue clay, and would likely be on schedule to deliver the good stuff the day after Josh left, and then grade and pack it between jobs when he moved machinery.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It was head down and ass up making preparations to accomodate their schedules. Josh worked one morning clearing brush and top soil, and finished up the next afternoon after the trees were down and the stumps ground. Les dropped off clay the third morning while I was fishing locally, and by the fourth morning, Chaz graded and compacted the site. At the end of it, we were ready to lay out the postholes, and I was ready for Lake Erie.

June 24, 2011

Hickory Dickory

"Adventure is a sign of incompetence" --Ernest Shackleton

Wax a car and 30 unforeseen events can jump between you and your intentions. Plan the first crossing of the Antartic continent sea to sea and pack ice can crush your ship before you land your party. When plans don't go according to plans, adventure begins.

Great care must be taken making the two cuts that notch the tree, the face cuts. They determine the direction of the fell (the lay), and they must mate up perfectly where they meet. They're comprised of a horizontal cut at 90° to the intended lay, 1/3rd of the way into the tree, and a 45° cut above it that completes the notch and ends exactly to the back of the horizontal cut. The hazard is a sloppy cut termed a Dutchman's notch, where either face cut extends beyond the other. It can cause lost control of the fell, resulting in barber-chairing (vertical splitting up the middle of the trunk), kick back (when the tree comes back over the stump) or a swinging Dutchman (when the tree pirouettes on its stump and away from its lay).

Keep in mind that loggers rank second in occupational deaths, ahead of Alaskan bush pilots, and behind only those who fish in high seas on icy boats during winter. So, when plans do go according to plans, when an amateur fells a tall tree against its lean near buildings, and the event unfolds step by step according to rehearsal, it may not rank with Ernest Shackleton's adventures at the Southern Cap by magnitudes to several powers, but at the end of the day, when the tools are put away, it still needs celebrated with feet up and a cold milk stout.

June 21, 2011

Building

About 25 years ago, Mike Grandominico gave me an estimate to build a pole barn back by the henhouse. He's still around and I still need the barn, so I called him back this spring and told him I was ready to start, but that I'd changed the site. Turns out he's changed his price, too.

A basic 24 by 24 structure with two enclosed 12 by 24 shed roof wings to either side, it will feature a spacious loft and a concrete floor. Built primarily to house my boats, tractor, lawnmower, Mary's car, misc. tools and equipment, and lumber, it will also provide an insulated room under one of the shed roofs, something I can heat and maintain as my hunting and fishing room, thereby liberating the one I use in the house to spare bedroom duty.

The site is off the Northwest corner of the shop, a tangle of briars, grapevines and small trees. A huge pignut hickory once dominated the plot, but five years earlier exactly to the day it came crashing down during a frightful windstorm, taking out the northern end of the shop, flattening my boat, and doing appreciable damage to both vehicles parked nearby.

A many-limbed shagbark hickory stands in the way of construction. It's leaning a bit toward the shop, too. Since the limbs prevented me from shooting a string over the top crotch and then roping the tree in the direction of the fell, I had no choice but to climb up 50 feet and tie it off. This entailed sawing away the limbs impeding my progress, and clearing the scaly bark as I proceeded.

My plan is to put the rope under tension from a come-along strapped to a tree in the direction of the fell, face cut the tree, plunge cut behind it, wedge it up good, and then cut the back strap. The wedges and the rope in combination should keep it away from the shop.

February 11, 2011

Of Rugs and Things

Mary argued against buying our first automatic washer and dryer some 25 years ago because she didn't want to abandon the control she had over a washload in her Maytag wringer washer. It's still in the basement, but she doesn't use it now. Next to it is a stained cardboard box of homemade lye soap that her mother made for it. Cotton clothesline rope still stretches across the ceiling floor joists where the clothes dried when the sun and warm wind wouldn't work. They're a backup plan now, and a box of memories.

She's somewhat a sentimental romantic, but much more a practical person, someone who values what's tested and true over what's currently fashionable. In this devotion she's unwavering. It's part of her strength and much of her beauty.

I was reminded of it this winter when I saw her in the back yard cleaning our braided rugs and snuck up to photograph her. She does it as her mother before her did. On a cold winter day, when the snow is a dry powder, toss the rugs out, cover them, broom the snow in, then sweep them clean. Do it several times, until the swept snow no longer turns grey. Hell with a vacuum cleaner. This does a much better job. Besides, my mother braided one of our rugs and hers made the other two. They deserve such respect.

January 29, 2011

First Hunt

Josh Fairchild and his son Javan took their first squirrel dog hunt on the last Saturday of the season. It was a hoot. They did all the shooting, and they did it with iron sights on their Ruger 10/22's.

I lost count of how many times Digger and Tricks treed, but it was a good day for squirrel activity. Warming temperatures and gentle breezes brought the critters out to bask in the sun on den tree limbs, and the thermals were right for the dogs to locate them through airborne scent.

At the first tree, just as he was bracing against a sapling for a 40 yard poke, I told Javan that if he didn't hit the squirrel square in the head, the shot wouldn't count and the squirrel would escape. I knew he didn't have much chance, but damned if he didn't roll the squirrel, and with a good shot, too.

Artemis, Greek goddess of the hunt and apparent witness, figured we no longer required her assistance, so she left us. Hers was a hasty appraisal. The next squirrel we bagged didn't have a bullet hole. Digger ran it down, caught and retrieved it after it figured its chances were better bailing and fleeing on the ground than dodging bullets and bark in the air.

At hunt's end, Josh and Javan decided that next year, one would carry a rifle and the other would back up with a shotgun. This resembles rebel boy squirrel hunting strategy as I've experienced it. Leaves stay on pretty much year-round in the South, so it's difficult spotting a squirrel that wants to stay hid. The preferred method of getting such a squirrel to reveal itself is to empty a clip or two into forks and likely hidey places, prompting flight. That's when the shotgunner steps forward. It suits rebel boys. They like to smell the powder burning.

Watching a father and son offer encouragements to each other, seeing them enjoy the hunt, hearing how much they were impressed by the dog work, and knowing they were looking forward to fried squirrel, biscuits and gravy, made for a memorable day and brought a joy that went beyond the fundamental satisfactions of the hunt. They'll be back next year. Meantime, should one become available, I'll be looking for an opportunity to shuttle a pup in Javan's direction.

January 8, 2011

Easy Money

Years ago I had a prescient dream that Leon Spinks knocked out Muhammad Ali, this when Ali was in his prime. No chance of it, according to the pundits. Outcome was almost as shocking as Buster Douglas' victory over Mike Tyson, except to me.

I wasn't a fight fan, and the contest wasn't on my radar. Why would I have such a dream except that God wanted me to make money? I tried to find a bookie. Back in college I knew a woman who placed telephone bets, but she was no longer available since divorcing her husband, and she never liked me anyway. I watched as Ali went down and my chance for an easy fortune evaporated. I didn't even bet 5 dollars with a friend.

Lesson learned. Years later I joined an online betting service in anticipation of someday having a similar dream. Maybe 5 or 6 years ago. Maybe longer, I dunno. Time's a blur now.

Anyway, I deposited $100 into the account and waited for inspiration. It's been this long and the bedside Post-it pad remains untouched, so long that the login details of my account were three computers ago, so long that I wasn't even sure of the service itself. But I did a little sleuthing yesterday, as the Oregon/Auburn game approaches, and reestablished contact with The Greek Sporting Service. Googled it. Found it because I remembered a Greek was raking vigorish from it. So I resurrected my account info with an email to the support link, and I'm poised to jump on the game Monday night, to increase my $100 by whatever the gamble provides.

Onliest problem is that I have no inspiration. There's not much money to be made here because the odds are not as great as when Spinks fought Ali. It's mostly money to be lost. But I want to bet anyway because I'm almost certain an Auburn blowout is coming, and the line is Oregon plus 2. It's a stone-cold, lead-pipe lock, seems to me. Meanwhile, my initial $100 continues to evaporate as the Guvmint prints new stuff for its needs. I'm losing ground. Help. Anyone out there had recent dreams about Auburn or Oregon? I want to push all in.

December 23, 2010

Less is sometimes less

After Chuck Ward from Arkansas, who could also skin a squirrel faster than any other man I've seen, Young Jamie Miller was the next-best off-hand shooter with a .22. He had a natural-born advantage over Chuck, though. He had three legs. Actually, it was two legs and three feet.

Except when purchasing shoes or requiring custom-sewn pants or dealing with the stares of passersby, he found advantages in it. Nobody could get around the side of a hill without slip-sliding better than Young Jamie. And nobody, except for Chuck Ward, who otherwise appeared normal in every way, could more consistently knock out a squirrel's eye without bracing up. He'd simply stand wherever he found the clearest shot, shoulder his .22, and ker-pow.

Young Jamie was also a philosopher of sorts. Not on a par with Epimenides the Cretan, or men like that. More like Dr. Norman Vincent Peale. Before he changed his mind about his extra left foot, or, more precisely, the right foot on his left leg, his outlook was always sunny. "It's only a handicap if you let it be." "Doesn't matter how you look on the outside, it's what's inside that counts." "Every dark cloud has a silver lining." "Everything has its purpose."

After undergoing "corrective " surgery this past summer, Young Jamie became normal in looks at the expense of his shooting ability. Although sometimes at night in bed, passing between the worlds of sleep and awake, he felt his missing foot itch, that was as nothing compared to the pain caused by its absence in the squirrel woods. Who could have foreseen the impact to his shooting, and, in turn, its metaphysical consequences? The tripod effect had steadied more than his hand. Even when he braced against a tree, using its platform for a third member, there was no denying he'd lost a foot, that his eye went with it, and so too his positive outlook.

We took our limit of 12 squirrels today over Digger and Tricks. Jamie was the shooter. He braced up in a wide stance on all of them, but could manage only head shots.

I'm guessing tonight a poignant gloom penetrates those unguarded moments before sleep. I'm guessing Young Jamie tosses a few times and drifts off thinking, "You never know what you've got until it's gone."

November 7-13, 2010

'Tis In The Season

"Thus, though we cannot make our sun

Stand still, yet we will make him run." --Andrew Marvell

The weather kept us off Lake Erie, Sunday, the 14th of November, ending my fishing season there. Swells from a blow on this shallow lake come high and hard upon one another, pounding against a boat and its crew. They turn dangerous in a moment. But the glorious week of Indian Summer before that, the brief warm, calm interlude we had? Oh, my!