Under the squirrel bigtop

©Dean Torges/The Bowyer's Edge™

If I have a totem animal, it's the squirrel. I might have wished for a wolf, or a tiger or some other majestic and large wild thing to shepherd my spirit through this world, but I ended up with a squirrel. You don't choose these things. They choose you. After all, if I wanted to impress friends and influence ladies, it's not something I would have wanted.

If I have a totem animal, it's the squirrel. I might have wished for a wolf, or a tiger or some other majestic and large wild thing to shepherd my spirit through this world, but I ended up with a squirrel. You don't choose these things. They choose you. After all, if I wanted to impress friends and influence ladies, it's not something I would have wanted.

But I'm ok with it because squirrels are ... well, squirrels. They are nature's free spirits, aren't they? A circus act out of control, a high wire act in clown's shoes. They are anarchists.

On the other hand, they are as possessive of turf as any circus ringmaster, insisting that everyone do everything under their supervision. They have so much energy and reckless abandon that God had to make them comedians so they wouldn't rule the planet.

Squirrels are tightly wound contradictions: volatile, short-tempered and self-absorbed clowns one moment, alert and furtive monarchs of all they survey the next.

Not to second-guess the Deity, but for just these reasons maybe Squirrel Rule wouldn't have been a mistake. We would certainly take ourselves less seriously—our spats would be over in minutes. We'd each be better stewards of our patch of earth and better judges of when to tuck tail and run, too—there'd be no shame in it—and our sense of adventure would sustain us when the mast crop fails. Then again, maybe that's just the squirrel talking in me.

Getting Dangerous

Groundhogs, cottontail rabbits and red and gray squirrels no longer hold our attention as they did when I came into archery. We're focused on big game now, primarily on the whitetail populations that have mushroomed across the eastern half of this country these past 30 years. Most modern archers only hunt small game occasionally, as a diversion. And squirrel hunting has suffered the most for it, at least partly because some of the best squirrel hunting occurs in November during the whitetail rut.

We are missing a ton of fun. This reality was expressed perfectly when I asked my buddy Tom Mussatto once if he shot squirrels while he was deer hunting. "No," he replied, turning my question inside out. "I shoot deer while I'm squirrel hunting."

I asked Tom because I wanted to know how far the big game bug had eaten into his sport. After all, haven't most of us become so intent on our whitetail mission that we won't shoot a squirrel, even when it begs to climb into our stew pot, for fear of spooking a "real" trophy? He's just a sideshow, this bit player rustling about beside us—an entertaining diversion while we wait for the center-ring, main attraction, right? So we turn into spectators, smile and feed ourselves fantasies about bucks behind the next bush.

The squirrel in me is insulted, and I won't be surprised when I read about archers attacked by angry rodents who've finally had it up to here with disrespect.

Of course, squirrels don't belong in everyone's bowl of stew. If you like being secretive about whitetail scouting and setups, obsessive about the soap you use, inflexible about the camo you wear and frightened of sweat on your clothes or gas pump odors on your boots, you probably can't like squirrel hunting. If each year you look beyond whitetails and book hunts for caribou, moose, elk and other such critters, squirrel hunting probably won't hold much attraction for you, either.

But if you consider the sound of your own chuckling to be a native woodland noise, if you regard arrows as gifts for the forest, if you don't mind crashing through the "deer woods" now and then to retrieve an arrow running away from you, and if you really, truly do like washing your mind and playing like a boy, perhaps the big game bug has not made a complete meal of you yet. Just maybe you've not bought into all the hoopla about what a modern archer should do and how he should act. Possibly you are still dangerous.

Ben Dare and Don Datt

Ben Dare and Don Datt

Squirrel hunting refines still hunting techniques. A squirrel hunter learns when to move and at what pace, and where to be when he is moving ... or waiting. Squirrels teach him these lessons by rewarding him with their presence when he does it correctly, disappointing him when he doesn't. A good squirrel hunter is a good bowhunter, period.

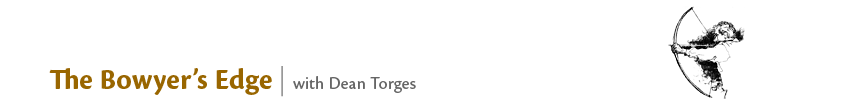

Two such bowhunters are Jerry Pierce and Tom Mussatto. Jerry is a nonpareil craftsman who spray paints his personal Choctaw Recurve black ("Barely a Ripple," TBM™, Nov/Dec 98). Tom, after 40 years in traditional archery, still labors wistfully after a durable self bow (http://members.tripod.com/~tmuss/OsageBow.html). Until he gets there, he bides time with a Howard Hill Big Five. Both are unassuming hunting archers who have perfected the aw-shucks shuffle because the spotlight bothers them.

Underneath, they are self-confident Illinois archers who share a passion for squirrel hunting. Both have been around the hickory tree a time or two, and both grin when they talk about it. They may be just Tom and Jerry on the surface, but, underneath, squirrels fear them.

Let's look at some of their techniques and equipment with an eye to becoming better squirrel hunters.

Equipment Choices

Both men shoot heavy bows, in the mid 60's for Tom, and in the mid 70's for Jerry. Squirrels don't require them, but the men use them for all their hunting and shooting. However, both use cutting arrowheads because the squirrels indeed do require them. Pound for pound, there is not a tougher, grittier North American critter, one that requires more killing, than a squirrel. Neither man uses blunts (judos or rubber blunts), considering them an invitation to wounded and lost game.

Both men devise economical, home-made heads and arrows fletched for silent, quick flight, made with minimal fuss. The idea is to take the shot when it presents itself, to get it past a squirrel's reflexes, and, excepting measures of safety, to let loose and never hesitate for fear the shot may break a valuable arrow or carry beyond recovery.

Jerry makes a two-blade small game broadhead. It's comprised of injector razor blade halves, mitred and epoxied as wings to either side of a field point. Assembly is speeded by a bank of tiny, precision jigs and clamps to hold blades and points in place while their epoxy bond dries (J.P. was a tool and die maker before retiring several years ago). Jerry started making these heads when injector razor blades were inexpensive and accessible. A few evenings at his workbench with materials, and he has a season's worth ready to go. Enough for passing out to friends, too, as is his habit.

Jerry makes a two-blade small game broadhead. It's comprised of injector razor blade halves, mitred and epoxied as wings to either side of a field point. Assembly is speeded by a bank of tiny, precision jigs and clamps to hold blades and points in place while their epoxy bond dries (J.P. was a tool and die maker before retiring several years ago). Jerry started making these heads when injector razor blades were inexpensive and accessible. A few evenings at his workbench with materials, and he has a season's worth ready to go. Enough for passing out to friends, too, as is his habit.

Sometimes Tom grinds 160 gr. field points to his purpose, but usually he depends on .38 cal. blunts with a triangular section of banding steel or a Bear bleeder blade inserted in a kerf sawed into the cartridge and shaft and then epoxied and pinned to the shaft with a small brad. The idea came from an American Bowhunter how-to article written by Vic Boyer over 20 years ago.

Magnus' small game heads are descended from Boyer's do-it-yourself plans. Magnus utilizes a heavier steel head with a precision slot machined in it to accept bleeder blades. Excellent refinements, which weigh out in grams about like most of our field points and broadheads, but cost more money, of course.

These are all deadly squirrel heads. Bleeder blades are replaceable and prove a little more durable than Jerry's razor wings when you recover one, but the wings are easily repaired at home should one break off.

One virtue to the home-made .38 approach is that the soft brass head makes the arrow more inclined to bounce back from direct tree trunk or limb hits, saving you another shot if the shaft can absorb the punishment. Its disadvantage for some of us is that the light weight forward affects arrow flight because it increases arrow spine. If your bow is critical of spine, as, for example, most self bows are, you may need to add weight to the head by various schemes or cut your shafts longer by an inch or two to reachieve performance.

The Reds and The Grays

Gray squirrels and red (fox) squirrels occasionally occupy the same woods, but they differ from one another in temperament and conduct. Grays, the smaller, are much more skittish than reds. They prefer deeper timber and make their way through their world as though they were fleeing a secret meeting. You very seldom find them, like fox squirrels, stretched out on a limb at the edge of a small woodlot, limp to the day and soaking rays. They seldom hold still for very long either, unless they are cutting nuts. As such, they offer far the more challenge for the bow and arrow.

Grays prefer denning inside trees, gaining access through holes from rotted limbs. Reds den inside, too, in winter and through the birthing season, but in the fall, during the most productive part of the hunting season, they live primarily in day beds or leaf nests. Grays don't much make leaf nests, so when you enter a woods or woodlot and see leaf clusters about the size of basketballs scattered about in tree tops, you can not only assure yourself that the resident squirrel population is red, but you can also come to some accurate conclusion about the density of its numbers.

Their barks are different, too. Fox squirrels actually do berate you: Chuck, CHUCKChuckchuckchuck... chuck... chuck. Grays often sound like an asthmatic forced to exhale, as though Mike Ditka sucker-punched the Godfather.

If you hear either bark, head toward him. He won't be far, and since he is distracted, focused on whatever has caused him to bark, you have a good chance of getting up on him undetected—unless, of course, he is barking at you.

Squirrels eat a variety of buds and seeds and grain, but their favorite foods are nuts. Before these nuts mature, they will work standing cornfields. Even after cornfields have been picked, they will search through them, sometimes dragging a scavenged ear back into the woods, sometimes even planting kernels as they go.

Regardless of species, a sound approach begins with locating their food source, which most often means "nut crop," and concentrating your hunting there. To judge recent squirrel activity in the area, look to cuttings (nut hulls evacuated of meat) under the canopies of such nut trees as shag bark hickory in the early season, followed by acorns, pignut hickories and then walnuts in the late season. The best of worlds puts you next to nut crops showing fresh cuttings located near den trees or leaf nests.

Following the Flow

Jerry begins his squirrel hunting in Missouri in August. Early season squirrels seldom provide shots on the ground, so an archer must be mindful of safety when he looses an arrow skyward. At this time of the season, Jerry uses arrows shortened an inch or so from breakage on the 3-D range and saved for this purpose. Since the best shot opportunities come while squirrels cut nuts, the shots therefore tend to be in the reaches of most tree tops. These arrows work because the archer generally shortens his draw shooting skyward.

|

|

During the early season, when squirrels spend most of their time in trees, the archer is advised to hunt second growth timber or scrub stuff that brings these squirrels into acceptable range. Such conditions provide the best chance of arrowing frenetic grays, which make up the bulk of Jerry's bag in Missouri. He considers those early season conditions ideal that meet these requirements and also provide him a dry stream bed for moving along quietly, with a few pockets of water here and there to attract squirrels.

Before hickories have matured enough to attract squirrels, Tom begins his early season hunts along corn field edges bordering woodlots. He purposefully avoids hunting too near dens because of the increased risk of losing a squirrel to a hole.

Beginning in November, when the likelihood of ground shots increases because a few frosts or heavy rains have brought leaves and much of the nut crop to the ground, stimulating squirrels to forage, Tom adds several Bodkins or MA-3's to his back quiver. He grinds about a quarter inch off their tip. This modification provides the shocking and cutting power characteristic of the best squirrel heads, and also makes them retrievable with a solid hit into a tree root or trunk.

An actual squirrel rut occurs in January and sends these critters chasing each other around tree trunks and across woodland floors with the same urgency that whitetails run through them in November. Nevertheless, the increased squirrel activity in early November gets the most attention from the small game aficionado. (Besides, January is a better time for chasing bunnies with beagles, but that is another article—and more arrows.)

Tom enjoys hunting reds, observing with a grin that they often hold their ground and scold you for missing your first shot. In this matter, he considers grays cowardly rather than smart, reds bold rather than foolish.

I witnessed Jerry center punch a knot hole high in a tree with a shot from his hip once. Saw the arrow obediently bounce back to his feet, like a trained dog, and watched while he nonchalantly kenneled it in his quiver, continuing through the woods, looking for another challenge. Without a word. Such men were born to hunt grays.

I prefer bold red squirrels myself.

What Are the Odds?

Squirrel numbers are up in the eastern half of this country, at least partially because big game availability has relieved hunting pressure upon them. So a good day of squirrel hunting will provide you with many opportunities to challenge your stalking skills as you maneuver for a shot.

Squirrel numbers are up in the eastern half of this country, at least partially because big game availability has relieved hunting pressure upon them. So a good day of squirrel hunting will provide you with many opportunities to challenge your stalking skills as you maneuver for a shot.

Not every close-quarter encounter provides a shot opportunity, though, and even then, as J.P. remarked, "If I'm batting .300 I'm doing ok." For this reason, Jerry fills his 6-arrow Selway quiver, and then grabs up an extra handful for each hunt. Carrying his baseball analogy further, he admits that "it's smart to know your strike zone and only swing at pitches which up your average," but in the same breath he will smile and admit that sometimes when the shot is open it's just fun to "go to the plate swinging."

Tom carries up to several dozen arrows in his Hill style quiver, an assortment of small game heads suited to the various tasks, and some broadheads for deer as well during November and December. He probably requires 100 arrows to get from August through January, and he may lose or break half a dozen in a day.

Tom hunts squirrels almost every day, sometimes for only an hour right around home. He will drive 50 to 60 miles on days off to hunt them. Jerry gets out 2 to 3 times a week, but must drive at least 15 miles to his closest squirrel woods. He, too, continues his squirrel hunting into November. Both men count themselves lucky to kill one or two squirrels a day, and both, on a few days, have done much better.

Changes

I like squirrel hunting a great deal. Many old timers do. The reason may be, as Tom told me, that it is the one facet of our sport that hasn't really changed much at all. Many modern traditionalists now go to the woods as deer hunters, carrying a stick and string, but loaded down with complex deer-catching paraphernalia—enough, almost, to require a check list. And if we haven't killed whitetails in numbers, at least we have read and researched and gizmoed them to death.

Not so for small game. Its pursuit provides simple, uncomplicated fun. Squirrels in particular won't have it any other way. Its gear requires only the elements of archery. And its attraction goes beyond nostalgic boyhood reflections, touching the joyful heart of archery past. From Chester and Howard back through to Maurice and Will. And before.

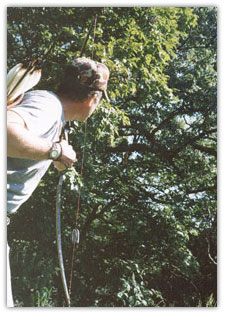

One of my favorite Ohio hunting areas is an overgrown farm that my brother-in-law owns. In addition to mixed oak and hickory hardwood stands, three large and tangled groves of mature Chinese chestnut trees, planted there for commercial reasons years before, act as squirrel and deer magnets. I imagine Southern pecan groves attract squirrels this way, too. Bushytails hurry about gathering them up before the deer eat them all, grabbing chestnut husks, studded with long, sharp, needle-like spicules, and carrying them off in their mouths as though they were green cotton balls.

The chestnut crop disappears within several weeks of its maturity, gone by the middle of October, but while it lasts squirrels are on parade. An advantage to me is that these trees don't grow much beyond 20 feet tall, so shots are not a stretch even when the squirrels work the branches. Another is that I can always go home with a sack of chestnuts.

Next to hickory nuts, chestnuts browned in a lidded iron skillet are my favorite table nut. Must be the squirrel in me. Floured young squirrel browned in an iron skillet and served with biscuits ain't too shabby eating either, especially with some brown gravy stirred up from the leavings. Must be the human in me.

Try it. You won't have to acquire a taste for squirrel. You won't have to develop a taste for chasing them with the bow and arrow, either. Not if you like to have fun and live dangerous.