Requiem for Jerry Pierce

©Dean Torges/The Bowyer's Edge™

I'm sure there are more self-effacing men in this world than Jerry Pierce. I don't know any. I like calling him J.P. for the irony of it, because it conjures up images of uppity 19th century tycoons and moguls who relaxed at the end of a day by counting business receipts. But I'm not misled by his burly exterior, either—by his huge arms and sledge hammer hands, his stooped posture, or by the slow, unflappable cadence of his speech and its hint of folksy, southern origins. Because sometimes a flash in the eyes or a twist to the grin gives a glimpse of a man living below the surface, of someone who sparkles and shines in hidden dimensions.

I'm sure there are more self-effacing men in this world than Jerry Pierce. I don't know any. I like calling him J.P. for the irony of it, because it conjures up images of uppity 19th century tycoons and moguls who relaxed at the end of a day by counting business receipts. But I'm not misled by his burly exterior, either—by his huge arms and sledge hammer hands, his stooped posture, or by the slow, unflappable cadence of his speech and its hint of folksy, southern origins. Because sometimes a flash in the eyes or a twist to the grin gives a glimpse of a man living below the surface, of someone who sparkles and shines in hidden dimensions.

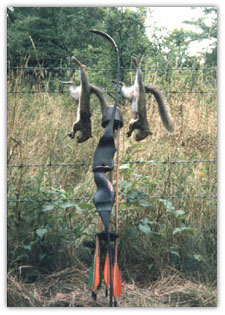

His personal bow is a metaphor for the man himself, and you will see his reflection in its craftsmanship sooner than you will know Jerry Pierce. Choctaw Recurves have appeared on magazine covers and within the pages of national sporting publications. They are the most sought after and highly prized of all modern archery tackle. He carries such handiwork with him to the swamp and timber, except that his bow is covered nock to nock with a coat of flat black spray paint from a 98-cent can. The palm swell and part of the thumb area have paint worn off the riser, providing just enough window to reveal a stratum of carefully matched tropical hardwoods, polished-and joined seamlessly. Just enough to provide a glimpse of a hidden dimension, of splendor living below a plain surface.

From, "Barely A Ripple" by Dean Torges

In a room with a few friends, Jerry Pierce liked sitting near the wallpaper and listening. In a room full of people, he sometimes required a curtain to hide behind, if others allowed it. Neither usually worked for him, at least not for very long. He was not shy, but he had a self-effacing strength of character that could not be dimmed under bushel baskets. It puzzled him even as it drew people to him.

If you look back to pictures of him as a young man, before his Choctaw recurves brought him an attention with which he remained uncomfortable to the end, you will see a sinewy hunter, a tall, strapping man who could just as soon plow through mountains as climb over them. And always with that same wry smile, the one that revealed an ornery, boyish heart.

Even these robust appearances screened the fact that from modest Mississippi roots he became so accomplished at the intricate skills of his trade during his employment as a machinist at Caterpillar, that by his retirement he'd risen in their shop to earning the highest hourly wage ever paid by his company.

Jerry Pierce held himself to a guarded standard, for whatever reason, that would bring most men to their knees. He had to be strong simply to survive his own demands on himself. This same uncompromising ethic and quest for personal excellence reflected through every facet of his life beyond his work and his recurved bows, from his absolute love for his wife, Bettie, to his complete devotion to his family, his children and grandchildren, to his conduct in the woods, his regard for his friends, and his appreciation of life's simplest pleasures.

Jan Adkins, a friend and artist, wrote me these words about meeting Jerry after spending a week with him during a recent hunt in South Carolina: "It took me a day to even see him, and longer to connect him with the intricacy of his work. And afterwards to wonder at the lack of flash and show. Look at the art world in which I work. Flash is often 90% of art's market value. Learning that an unassuming man built those recurves, devised their geometry and created a unique style within their narrow boundaries was like discovering that the FedEx delivery guy built everything he brings you."

Jerry Pierce was more comfortable with pretending to be the guy who delivered his Choctaw recurves. "Here, I found this," his manner said. "It had your name on it. Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain."

None of us knew the man behind the curtain nearly well enough. He rarely talked about himself, and his words on that subject usually tried to deflect attention away. Even his posture and the way he would look at you without moving his head indicated he preferred hiding behind himself to being on display. You could see it in the slouch that he adopted as his Choctaw Recurve brought him more and more spotlight attention, a slouch unfamiliar to the less encumbered and younger Jerry Pierce.

It was always with a quiet dignity and a generosity of spirit that he conducted himself, and in that language he spoke volumes. He was in many ways an innocent who thought first of friends' and loved ones' needs, requiring no more reward for his generosity toward them than his own private and personal satisfaction. Some of his friends tried to run interference for him because this innocence afforded him few protections against men who would pry into him for his bows. We had long talks about it, and an especially memorable one with him and Jim Reynolds and me took place a few months before his death. He knew what was going on (innocent isn't the same as stupid), but he shrugged his shoulders as though he were helpless to be more or less than who he was.

I tried once to run interference for him. It just didn't work. I'd enlisted his wife Bettie and some of his friends to put a full court press on him to get a physical check-up. He had been much too long without one. His response was to challenge me to a push-up contest in front of a small audience of friends the next time we hunted together. After goading me with his sly grin, he went to the floor and did twenty. Military style. A little more dramatic than Jerry's usual method of making a point, to put it mildly, but consistent with his letting actions speak for words.

It took me a month or two to understand that episode, its motive and message, and when I finally did make the connection, I had to submit and respect how he decided to do things—his way. I'd made my point, too—he knew how we felt about him neglecting himself. We are left wondering now if the full-court press gave up too soon. But, Lord, I couldn't have survived a bow and arrow knot hole shoot-out after a 26 mile swamp run preceded by a swim through alligator waters. And it would have come to that had we continued to press him. He may have been an innocent, but he was a knucklehead, too.

I did not let him build me a bow when he wanted to several years ago. It was my way of relieving pressures on him to make and give away bows, pressures which sometimes weighed upon him to the extent that they sucked the joy of making bows from his life. It was my mistake, though — another silly way of running interference for him. His blessing was to give to those he wanted to give to, and it was not my place to refuse him or to interfere. Those few archers privileged to own Choctaw recurves, and those several organizations chosen to receive his bows as auction gifts understand this, and humbly accept the honor. That is also why I'm pleased that we recently came to an agreement about swapping bows, and that he glued the riser together for mine before he died. He left it squared up on the table of his spindle sander.

He told me once that he felt John Rook would see and appreciate the wood in the bow he built for him even through his blindness, so he built John the prettiest bow he could with the best wood he had. Told it as a matter of fact, with no mystery to it. You had to believe him. I can see into the finger-jointed African Blackwood riser that I have now, and realize what a beautiful bow it is, too. A dormant, unpolished treasure, I can see the man invested behind its curtain of thoughtful wood choices, precise, complex marquetry and uncompromised glue joints. It will remain in this state, squared up and true, a fitting and perfect memento. Should the fates allow, I will finish the bow I intended for him — the prettiest bow I can make with the best wood I have.

So I think about knowing Jerry Pierce, the gentle man behind the sly smile, the man with the sledge hammer hands and the dazzling 74 lb. Choctaw recurve screened from view with cheap black spray-paint. And I wonder as well how perfectly he saw us, too. Did he realize how much his inner strength set him apart in our eyes? Really, I don't think so. I don't think he had much clue how it warmed the people who stood near him, either. It would surprise him, probably embarrass him, that the world seems a little colder to us now, that we'll all be slouching for a little while.

Tom Mussatto, a long-time Illinois friend of Jerry's, wrote these wistful thoughts while surveying a bleaker landscape following Jerry's death: "I mostly relate to those old Oregon boys, to the way they hunted, the way they enjoyed their archery, their total investment in their tackle, and the way they were pretty low key about the whole thing. I would have loved to have lived in those times."

"Me, too," I wrote back, following the thought to a shared understanding. "Jerry Pierce in his heart and manner was an Oregon boy. Insofar as we knew him, we did live in those times."

Vitae

Jerry Oren Pierce was born in Union, Mississippi, May 13, 1935, and died March 15, 1999. On July 10, 1963, he married his childhood sweetheart and the love of his life, Bettie L. Wells, in Philadelphia, Mississippi. She survives him in Elmwood, Illinois, where they have lived these past 40 years, rearing a daughter, Angela Sander of Peoria, and two sons, Eddie of Steamboat Springs, and Lenny, of Philadelphia, Mississippi. He also leaves behind seven grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.